The culture-biased IQ test of bureaucracy

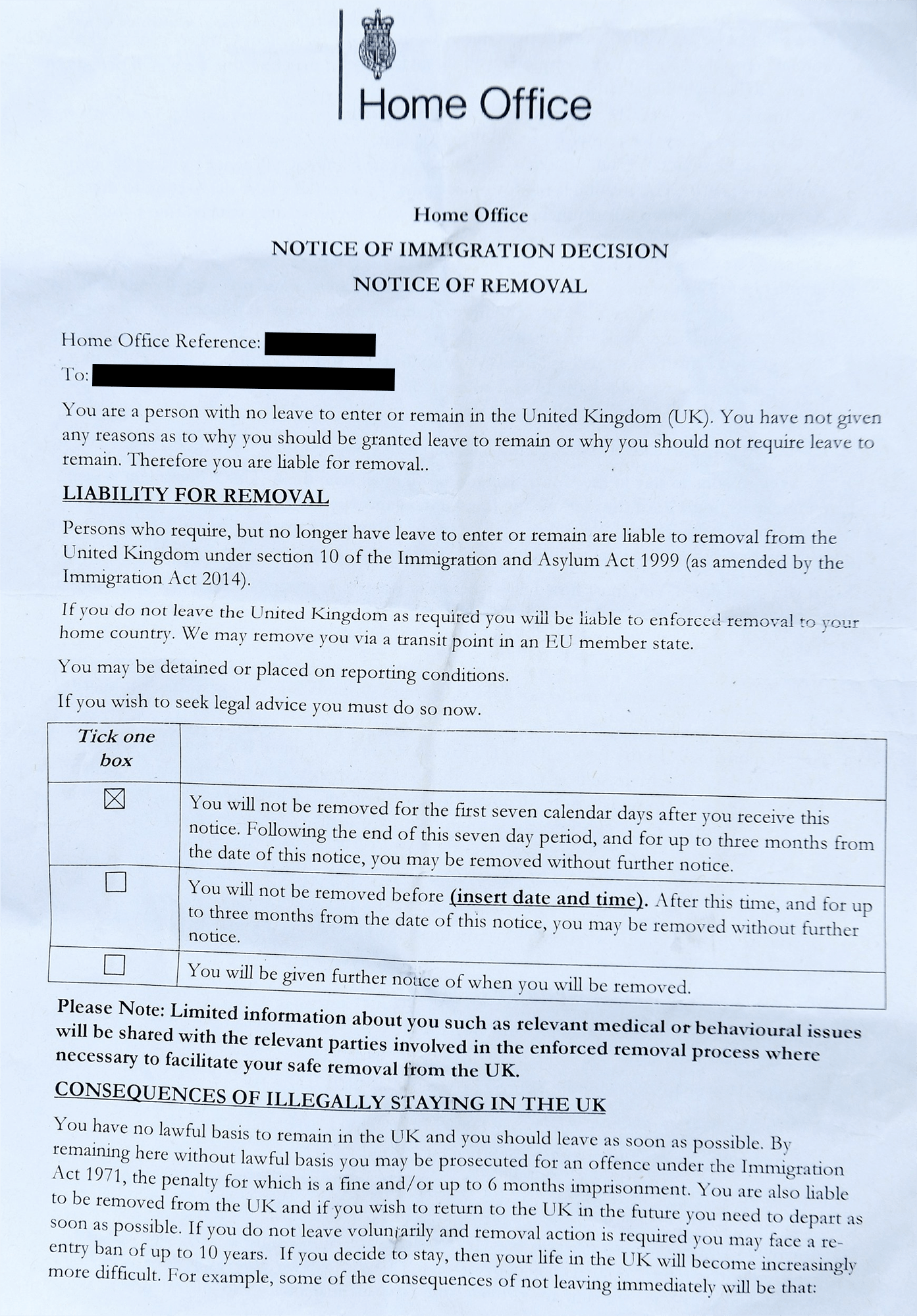

The stakes are high. The letter1 from the UK Home Office states that on any of the next 90 days you will likely be forceably removed from the country. You have a genuine right to residency, but despite doing your level best and diverting as much of your income as you can afford to solicitors, you have failed in evidencing this to your government.

You have one week to convince someone at the Home Office to overturn the decision.

This situation should never occur, but it does every day2. Why?

-

Complexity begets inaccessibility.

The system as a whole, comprising the legal system, social services, charities, companies and any other bodies a case requires interaction with, is architected, built and maintained by overwhelmingly Western-educated people who have dealt with such a system their entire lives. For those of a different background, it can prove a Sisyphean challenge to grapple with it sufficient to provide themselves even the most basic of representations, particularly if they have not received education, are not functionally literate3 or fluent in English. -

Lack of coverage of publicly-funded support (e.g. Legal Aid or Citizens Advice).

Support is Balkanised across multiple agencies, each defining their own limited scopes – inevitably cases or aspects of cases fall through the gaps. Where cases are eligible for help, “advice deserts” exist across areas of the country where bureaucracy and uneconomic rates of pay have turned solicitors away from undertaking publicly-funded work4. -

Solicitors lack the economic incentive to provide strong representation to their client.

Clients’ or Legal Aid’s limited budget necessitates low-touch, largely cookie-cutter work. It’s uneconomic to spend hours gleaning information from a client who may not be well-versed in paperwork and bureaucracy, and may not be literate or speak English, to gain the comprehensive holistic understanding of a case needed to provide strong representation.

All of these I’ve bumped into working with people in the above and similar scenarios. Skills that readers of this blog will undoubtedly take for granted like “writing a letter” or “making a request to a government agency for information” or “communicating the facts of a case so a lawyer can help you” are not innate.

For far, far too many people, what this adds up to is that their rights practically speaking do not exist.

Of course this isn’t limited to enforced removals – the area I happen to have some insight into – and often the fate is worse than being flown back to your former home country.

A case made infamous by the remarkable documentary Fourteen Days in May is that of Edward Earl Johnson, an innocent man falsely convicted and executed by the state of Mississippi. A victim of the inaccessibility of the legal system, without funds he relied upon state-appointed defense attorneys that were unable to provide the competent representation that would have saved his life. The complexity of the legal system intersected with their economic disincentives to produce a litany of errors, as documented5 at the time by public interest attorney Clive Stafford Smith.

In lieu of a magic money tree6, some lessons to improve the situation:

-

User journey and user experience must be valued across the whole of government and the legal system as they are at consumer technology companies such as Facebook.

More care needs to be given to the perspective and experience of the user of the various services to simplify the system they have to interact with. In spite of its incompetent IT implementation7 Universal Credit is a step in the right direction in its aim to simplify the interface in place that the user has to care about.

Moreover there are less obvious changes that need to be made as well, such as requiring state schools, GP and dental surgeries to have mechanisms in place to provide sufficient documentation for parent with dependent child cases. I recently had to rely upon The Education (Pupil Information) (England) Regulations 2005 to have an urgent request taken seriously by a school dragging its heels, which should not have been necessary.

-

Citizen efforts to improve the user experience of the system.

I believe there’s massive scope here. The best example we have is DoNotPay, started by a well-to-do Brit who wanted to shirk parking fines, it’s a chatbot that has saved users an estimated £12m in fines and has since expanded into helping refugees claim asylum. By interfacing with users in plain English with a free, simple-to-use chatbot flow to get the necessary information, it can then draft the necessary forms and documents before submitting them without having to expose the user to the complexity underneath.

All such efforts are very limited in scope thus far, but I think that this will be a very interesting avenue to explore to parlay public and community funding into a better self-serve legal system in many specific but common cases.

-

Effective altruism can be remarkably effective in the tiny fraction of most egregious cases.

The aforementioned British attorney Clive Stafford Smith worked for the Southern Center for Human Rights and later went on to found the legal charity Reprieve, in the process saving all but 6 of the over 300 prisoners facing the death penalty in the United States that he represented. This is a substantial mitigation of the flawed systems requiring relatively modest investment.

Regarding enforced removals, there have been various cases where a decision has been successfully challenged at the last minute after raising sufficient attention on sites like Change.org to make not overturning the decision indefensible for the Home Office8.

However, this is only able to help a tiny fraction of the people who suffer from the inaccessibility of the legal system, where the outcome is particularly repugnant or sufficiently compelling and marketed to gain attention.

Conclusion

We are faced with a choice: make the system more accessible through increased funding, simplification and increased attention paid to the end user experience; or the idea that we’re a country of citizens with equal and inalienable rights will continue to be just a myth, as practically speaking, for far too many people, those rights do not exist.

For further exploration of redistributing legal labour to reconcile the divergence of the law as it is written and as it is lived, read Policing, Mass Imprisonment, and the Failure of American Lawyers by Alec Karakatsanis, founder of Civil Rights Corps, a non-profit organization dedicated to challenging systemic injustice in the American legal system.

-

Which will look something like this:

-

421 of 687 people issued Removal Directions via chartered flights out of the UK through 2017 were withdrawn “through last minute legal actions or fresh representation or withdrawn for any other reasons”. See the Enforced removals and deportation by charter flight 2016-18 request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

Pending request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000: Enforced removals that were overturned. ↩

-

Stricter than literacy, functional literacy means “reading and writing skills that are adequate to manage daily living and employment tasks that require reading skills beyond a basic level”. 17% of adults in England do not meet this bar according to the International Survey of Adult Skills orchestrated by the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). ↩

-

Documented in the Joint Committee on Human Rights’s report Enforcing human rights:

“Take Devon and Cornwall. There is one small legal aid provider in Plymouth, as far as I understand it, for immigration law. It therefore deals with anyone in the entire region who has problems arising within that sphere.”

There are many examples of solicitors’ firms ceasing (generally with reluctance) to undertake legal aid work in order to keep the firm in business. The Law Centres Network told us that legal aid work is barely viable for non-commercial providers (who cannot subsidise it).

“CCMS—the client and cost management system—is an absolute disaster from the lawyer’s point of view; [ … ] This is the system that is used to administer legal aid. It is designed from the Legal Aid Agency’s point of view. In no way is it an effective system, and unfortunately a lot of lawyers are just walking away from legal aid because they do not want to be bothered with the bureaucracy; they will go off and do private work.”

-

See the petition for clemency and petition for writ of habeas corpus. ↩

-

A phrase used by the UK Prime Minister Theresa May in highlighting the naïveté of expecting public spending increases without hitting the public’s tax bill commensurately. Magic Money Tree – YouTube ↩

-

A natural corollary of involving Accenture, IBM, Hewlett Packard et al. ↩

-

Two NHS doctors who faced enforced removal saw their decision overturned after tens of thousands petitioned their MPs to act here and here. ↩